1. Introduction

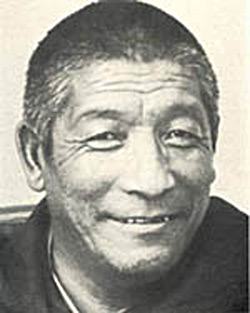

Geshé Rabten (from The Life and Teaching of Geshé Rabten).1

Geshé Rabten (dge bshes rab brtan, 1920-1987) was a renowned scholar-practitioner of the Jé College of Sera Monastery. He was born in Kham, eastern Tibet, and for twenty years he made Sera his home. After completing most of his studies there, he fled Tibet in 1959. He did his final examinations in Buxador, India, and obtained the degree of geshé lharampa. Geshé Rabten became abbot of the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery in Switzerland in 1975, but he had already been teaching European and American students since 1969. In what follows, Dr. Alan Wallace, one of Geshé Rabten’s first Western students, interviews his teacher. The portion of the text excerpted here begins just after Geshé Rabten arrived at Sera from his home-region of Kham. This wonderful selection gives you a real sense of what it meant to be a Sera monk, and provides you with a glimpse of the zeal, dedication and warmth of an amazing contemporary Buddhist teacher.

From: Geshe Rabten, The Life and Teaching of Geshé Rabten: A Tibetan Lama’s Search for Truth, trans. and ed. B. Alan Wallace (London: Georges Allen and Unwin, 1980). With the permission of Dr. Wallace.

Read more: http://www.thlib.org/places/monasteries/sera/#essay=/cabezon/sera/lifeofseramonk/#ixzz0WuvD8PDT

2. Initial Training in Sera

Disciple: Were you able to begin formal studies and to fully enter the monastic discipline as soon as you were admitted into the monastery?

Geshé: I was allowed to attend lectures by my guru; but I had to memorize some important scriptures before being allowed to take part in the debating sessions. I got up at four o’clock every morning, went out to the stone courtyard in front of the main assembly hall, took off my shoes, cap and upper cloak, and made many full prostrations until sunrise. To get rid of my delusions, my teacher instructed me to recite a short sutra of confession, the Vajrasattva purificatory mantra, and the prayers of taking refuge, all while making prostrations. He told me it was necessary to eliminate obstacles for one’s spiritual studies and for the practice to be fruitful. I was persistent in doing these preliminary practices, even during the winter. In the biting cold on winter mornings, the skin on my hands and feet would split and bleed. But despite the physical hardship, I was not discouraged. In fact, I felt happy when I reflected that this was a means for purifying mental obscurations and the imprints of former harmful actions. I was not the only one carrying out such practices – the whole courtyard was filled with other monks doing the same thing, and this was very inspiring. Then at sunrise a conch shell would be blown, and all the monks would assemble in the main hall for the morning prayers and tea. Afterwards, all the new monks, including myself, returned to our quarters and swept and cleaned the halls, while the older monks were debating. We did not do this simply because we were forced to. Rather, we reflected that such work aids one’s Dharma practice in this life, and yields good results in future lives as well. After this we memorized the scriptures required for entering our college. There were three colleges in Sera - Sera Jhé, Sera Mé and Sera Ngagpa. Mine was Sera Jhé; in it alone there were over six thousand monks at that time. At the beginning, since I had never done such studies before, memorization came very slowly and reciting texts in the presence of my teacher was difficult. I was making all these efforts so that I would be allowed to begin studying the great treatises. Thus, I felt no hardship.

Just before noon, I attended an assembly in the hall of our college; then we took tea and barley meal. Afterwards I would return to my room to study. Whenever my teacher had some spare time, he would give me very basic teachings on philosophical analysis. In the evening, around six o’clock, all the monks would return from debating; those from my house would immediately hold a special gathering for prayers, which I attended. When this was over, all monks were required to go to their respective teachers for lessons on philosophical analysis. There was one old monk who was the disciplinarian for our house; he would then come around to all the cells to see that no one was sitting inside loafing. Every night I would have my lessons, along with other new monks. As the light was very dim, the teacher could not read; so he had to teach by heart, and the disciples had to try to remember all that he said. Geshé Jhampa Khedub had a very special way of teaching. For about three days he would instruct us in logic; then he would leave this for a day, and relate some accounts from the Jātaka scriptures describing previous lives of Lord Buddha. Or he might tell us the life stories of sages and realized meditators who had gained great spiritual attainments. It was so peaceful, so beneficial, to be in his presence that I never became bored or tired. The times with him were always too short. The class regularly lasted two hours; then all the other students returned to their rooms, but I would normally stay with him until about eleven o’clock. I would insist on making his bed, then take my leave, shutting the door quietly behind me. On my way back to my room, I was allowed to wear my shoes if there were monks sitting in the halls reciting scriptures; and if I was not tired, I would join them. But if they were practising meditation, I had to remove my shoes and walk very softly, in order not to disturb them.

Disciple: Were you ordained as soon as you entered the monastery?

Geshé: No, I waited a couple of months, thinking to follow whatever advice my teacher gave me. Then he told me it would be good for me to receive the novice vows from Phurchog Jhampa Rinpoché, who was recognized in Tibet as an emanation of Maitreya Buddha.

Disciple: What is involved in becoming a novice?

Geshé: Three transformations are needed. The first is to change one’s attitude. By the force of renunciation, one must change and elevate it from that of a householder to that of one who is earnestly concerned with the Dharma. The second is to alter one’s external appearance by donning monk’s robes and having one’s head formally shaved. And the third change is to take a religious name. In addition one must receive the novice ordination from a guru. I was given the name Jhampa Sherab, whereas previously I had been called Tadin Rabten. But now most people still use my former name. This is the procedure of becoming a novice; but more important is the actual keeping of the thirty-six primary commitments, and about two hundred and forty other ones.

Disciple: After you had entered Sera, how long was it before you were allowed to begin debating?

Geshé: About two months. During that time, as I said, I memorized the scriptures and prayers that were needed to pass the oral entrance examination. Then, together with many other monks, I was examined before the abbot and the disciplinarian. With many of the others, I was successful and was allowed to enter the central debating courtyard.

Disciple: After passing this examination, do all the monks follow the same course of study?

Geshé: Yes, all who study in Sera work up to the degree of ‘Geshé’; and to attain this, one has to pass through at least fourteen, and sometimes fifteen, classes. Listed in order, these are:

- Beginning Collected-Topics

- Intermediate Collected-Topics

- Advanced Collected-Topics

- Beginning Treatises

- Advanced Treatises

- Beginning Separate-Topics

- Advanced Separate-Topics

- Perfections

- Beginning Mādhyamika

- Advanced Mādhyamika

- Beginning Discipline

- Advanced Discipline

- Phenomenology (abhidharma)

- Karam. A detailed review of discipline and phenomenology

- Lharam. A final review of the Five Treatises. Only two from each college can graduate from this class each year.

There is no way of skipping any of these classes. This is a well-developed system, beginning with basic logic and working up to the great scriptures of India, including both the sutras and commentaries. Just as the alphabet and grammar are studied in primary school, to enable one to understand higher topics later, so logic is studied to train the mind in subtle reasoning, thus enabling one later to appreciate the great scriptures.After developing his intelligence and discriminatory powers in this way, a monk is able to apply as many as twenty or thirty logical approaches to each major point of teaching. Like monkeys that can swing freely through the trees in a dense forest, our minds must be very supple easily to comprehend the depth of the concepts presented in the scriptures. If our minds are rigid like the antlers of a deer, which are cumbersome when sitting or standing, we will never be able to reach this depth.

Disciple: What was the first subject you studied?

Geshé: We were first taught the easiest subject - the relationships between the four primary and eight secondary colours. They were explained carefully; and we learned how to apply simple logical reasoning to them. Debate sessions were held during the day. At noon all the monks would return to their rooms to eat. While the others were eating, I would go to my teacher and tell him what I had learned and what problems I had encountered in debate. Then he would give me private instruction and sometimes food as well. While the subject of colours and their relationships is very simple, it is the manner of phrasing the question in debate that trains the mind. This becomes very interesting and challenging. Once we had mastered it, our intelligence developed somewhat; and we were then taught about the five aggregates of a person, the six senses (including the mind) and their objects, and the eighteen kinds of phenomena: which are the six senses, the six objects and six consciousnesses. Then we really expanded our faculties to explore detailed classifications of all impermanent and permanent phenomena. We studied the two realities according to the Vaibhāṣika and Sautrantika philosophical schools, and the three types of objects of knowledge. These consist of the objects cognized by bare perception, those perceived by inference (e.g. emptiness, impermanence and the fact of rebirth), and extremely concealed objects, some of which can be cognized by scriptural inference, while others are known solely by a buddha’s mind. We dealt with cause and effect and contributing circumstances, the six divisions of causes, and the four types of effects. We made an extensive study of the two types of relationships and the four types of mutual exclusivity. We further studied the classifications of positive and negative entities. The former are those that are cognized by means of negation. An example of this is space, which is defined as ‘the absence of obstructing contact’. A positive entity is simply a phenomenon that is not understood through negation. We investigated the two types of negative entities: complex and simple, the former having four types. This is a very important subject. After this, we studied the different kinds of consequential reasonings. These are a dialectical means for dispelling mistaken views. In debate they are used to reveal contradictions in the successive assertions of a person holding incorrect views. Then he is led again, by means of consequential reasoning, to a correct understanding of the subject. There are also eight and sixteen ways of pervasion, in relation to consequential reasoning, and these too are studied. During the Collected-Topics classes, we covered a vast number of other subjects. Among these was the study of subject and object, of which there are many types. After sharpening one’s intelligence during the Collected-Topics classes, one studies the nature of the mind, which is of great importance. As there are many categories of mind, so too are there many types of perception. The mind is divided into the two categories of consciousness and mental factors, the latter having fifty-one divisions. These fifty-one are yet further classified. We studied all these divisions carefully. There are also different types of consciousness, such as mental, sensory, conceptual and non-conceptual perception. Mind is further categorized into ideal and non-ideal cognition. In the former category are the two sub-divisions of bare perception and inference, both of these having four divisions. There are also five types of non-ideal cognitions.After proficiently studying the mind, one explores a number of subtle concealed-entities, by training oneself in the three types of reasoning. Each of these also has many divisions, all of which we covered. By this training, one is able easily to understand very difficult topics in the great scriptures and treatises. In order to recognize a correct reason, one must study its three aspects. While studying the types of mind, one examines both the Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna discussions of this subject. Although this training is primarily given on the basis of the Sautrantika system, all the philosophical schools up to and including the Svātantrika are also discussed. All these subjects are examined by analysing their defining characteristics. I would get depressed sometimes, feeling I did not know and was not learning anything. When this happened, my teacher, again acting with great wisdom, would teach me some very difficult concepts, then make me debate with older monks who were studying higher subjects but who were not so learned. My depression would vanish when I asked them questions they could not answer.

Disciple: Would you describe how a debate is held?

Geshé: Perhaps the most obvious characteristic is the hand gestures. At the opening of a debate, you first say ‘dhīḥ’, the seed syllable of Mañjuśrī, as you clap your right hand on the left. Then you draw the right hand back, and at the same time put the left hand forward. This motion of the left hand symbolizes closing the doors of the three lower states of rebirth; drawing back the right hand symbolizes one’s wish to bring all sentient beings to liberation. But to fulfil this wish is not easy. You must have great knowledge and wisdom; and for this you recite ‘dhīḥ’, asking Mañjuśrī to pour down a torrent of wisdom upon you. In ordinary conversation, the only words that really affect others are those that are either very pleasing or bad to hear. In the same way, the seed syllable ‘dhīḥ’ has a very special effect upon Mañjuśrī; such that he, out of his great compassion, blesses us with wisdom and understanding. Debating involves two people. The answerer sits while the questioner stands, as if the latter had doubts and was respectfully approaching the other for answers.

Disciple: How did these Collected-Topics studies affect your level of intelligence?

Geshé: By the end of these classes, I felt that my power of reasoning had developed, though not completely. In my college there were seventeen or eighteen monastic residences, and mine was called Tehor House. In it alone there were 115 monks who started in the same year as I. There were roughly ten to fifteen teachers to instruct these students; I was honoured by being elected their leader. A class leader had many responsibilities, such as opening debate sessions in the morning and evening, deciding how long they would last and making sure that everyone attended. On the night that I was first to assume these responsibilities, I was sitting with my guru in his room. Around nine o’clock as I rose to go down to start the debating session, I suddenly fainted and fell to the floor. When I regained consciousness, my teacher sent someone to replace me that evening. Then he taught me ‘The Hundred Deities of Tuṣita’, a prayer to Jé Tsongkhapa, along with his mantra. He advised me to recite the latter 100,000 times as an antidote for my malady. Whenever this disorder manifested itself, it rose from the lower part of my body; and if it reached my heart, I would faint. But when I felt it rising, I would start reciting this mantra; after I had done so about twenty-five times, the symptoms would disappear. Eventually this took only eight repetitions. I recited it 100,000 times; then my teacher told me to do so again, after which this ailment never returned. Thus, I have seen from my own experience how powerful this practice can be if one has faith. Sometimes the Tsishar Geshé, the chief monk of our house, would come and recite a text that we were studying. Whenever this happened, I had to repeat what I had memorized in his presence without making any mistakes. Another of my responsibilities as leader was to invite learned monks of higher classes to debate with us, in order to sharpen our intelligence. I had to answer all their questions first, and I was also the main one to ask them questions. I further had to send monks from my class to debate with other classes.

Disciple: How long did it take you to complete all the Collected-Topics classes?

Geshé: Altogether two years, but it takes most monks in other monastic houses three years. Before being allowed to graduate, I had to pass an oral examination in front of all the monks in our house, a total of more than five hundred. As class leader, I had the special task of standing before them all and slowly and melodiously reciting the biography of Sakar Tulku, who was the chief monk of our house. This took more than an hour. Then I had to debate in front of all of them. This can be really nerve-wracking. It is not like examinations in other institutions, which you can do alone with plenty of time to think. In a debate answers must be given as soon as the question has been put. You stand before all those monks, some of them very learned; and all their attention is upon you. When we were in the last stage of the third of the Collected-Topics classes, our class debated for two weeks with the next higher class in our house. On alternate days, one of our better students was chosen by the Tsishar Geshé to answer questions in debate with monks of the higher class. Then on the other days, one of the latter would answer questions that we asked. This was very difficult, for they were much more learned than we.

Read more: http://www.thlib.org/places/monasteries/sera/#essay=/cabezon/sera/lifeofseramonk/s/b2#ixzz0WuvVobAc

3. Monastic Life and Education

Disciple: You mentioned that Geshé Jhampa Khedub eventually returned to his home province. When did this happen?

Geshé: Geshé Jhampa Khedub was my teacher throughout all the Collected-Topics classes; but soon after I had completed them, the monks of Dhargyé Monastery in Tehor, Kham, insistently requested him to come and be their abbot. Finally he agreed. By that time, I felt that he had opened my eyes, but not shown me what to look for. When he left, he kindly sent me to a very wise teacher, Chötsé Ngawang Dorjé. This was his oldest disciple, who was extraordinarily learned and compassionate like himself. As he was getting ready to leave for Kham, I was extremely ill with fever and could not sit up on my bed. When he came down to my room, I tried to rise but was so weak and dizzy that he told me to lie still. It was all I could do to reach one arm up and give him a scarf which I had ready. He earnestly prayed for my recovery and success; then after he left, I pulled the covers over my head and wept. It proved to be a great blessing for the territory of Kham when my guru returned to our home province. On the way, he relieved the hardships of the inhabitants of many districts, by means both of the Dharma and his supernormal powers. After arriving in Tehor, he turned the Wheel of Dharma in all the regions of this district and brought all their inhabitants, young and old, to the path of joy. Specifically, in Dhargyé Monastery he had a large number of new meditation huts constructed. He then urged many monks to practise meditational retreats for several months, during which they never went outside. While they thus devoted themselves single-pointedly to the path of the sutras and tantras, my teacher arranged for the monastery to supply their material needs. As soon as one group of monks had completed their retreat, he sent up another group. By such means he brought about great progress in terms of meditation. Furthermore, for philosophical training, he initiated many classes in the monastery in which the sutras and their foremost commentaries were memorized, and others in which large numbers of students were trained in this philosophical discipline. He had all these as well as others gather in a special courtyard, and debate on the meaning of the scriptures; and he made the monastery support them and their teachers. By such means he greatly served the Dharma and the needs of living beings. Due to his influence, there were some students who could recite from memory thousands of pages of the scriptures; and many others progressed well in the philosophical training. To sum up, it was as if there was no one, man or woman, young or old, who did not enter the progressive path of Dharma. It even stirs my heart to remember my compassionate guru, who reached the ultimate degree of learnedness and meditative ability, not to speak of actually seeing him or hearing his voice. Thus, even to this day, my heart aches to meet him again.

Disciple: Did your father continue to send you food and money during these years of study?

Geshé: No, this was not very feasible as my family lived so far away. Although none of my relatives sent me anything, I did not borrow because I knew I would be unable to pay them back. As a result, I remained poor until after I had become a senior monk. But I continued my studies, and by remembering the purpose of my coming - to cultivate my mind - I did not become discouraged. Through all these years of poverty, I never had anything that was good. Since my shoes always had holes, I often walked barefoot on the cold stone floors. For several years I was so ill that on returning from a debate, I sometimes could not climb the stone steps leading to our house, but had to crawl up on all fours. Some of the ailments I have now can be traced to those times. I had only ragged clothes that other people had given me, and since I was not concerned with my appearance, instead of sewing the torn pieces together, I joined them with bits of wire. When I needed another piece of clothing, I would buy it from small merchants’ stalls that were set up just outside the monastery walls. They would sell at a low price the garments of monks who had died.As for food, I had so little money that I rarely drank real tea, but bought instead herbs that just turned the water dark. For kitchen utensils, I had only one clay pot; but then the cooking I had to do was very simple. I could not afford barley meal, the most common food in Tibet; but instead bought pea flour, which is much cheaper. Sometimes I could not even get that for five or six days in a row; for I lived solely on the charity of others. When I was given a few coins, I would buy a fist-sized piece of fat, dissolve it in boiling water and drink it. Then I would feel so nauseous that any desire for food would leave me. Sometimes when I was very hungry and had nothing to eat, I would go to the room of some of my friends, hoping they would share their meal with me. But on some occasions, they would be out, and I had to return with an empty stomach and a downcast mind. At other times when I went to their room, I would feel too embarrassed at the last moment to ask for food, and I had to return as hungry as before. I have never forgotten those who kindly helped me during my poverty. There was one incarnate lama, Gomo Rinpoché, now living at the Tibetan Homes Foundation in Mussoorie, who often gave me balls of barley meal, which made me very happy. I will also never forget one occasion when another monk made up a pot of nettle soup, drank it, then gave me the pot to clean. I managed to scrape off a little bit of soup that had stuck to the sides of the pot; I savoured it as if I had been given a full meal. During these years, I became very thin and weak, and my skin turned green. So, as a joke, my classmates nicknamed me ‘Milarepa’, but only because of my appearance, not my attainment of wisdom or insight. Throughout the year, there were a number of interims, during which there would be no monastic assemblies or classes. Then I would find it very hard to get enough to eat. During one of these periods, a monk came to my room with a fist-sized parcel covered with wax; he told me that it had come from the north. Even before he left, I hurriedly opened it and found two pieces of boiled meat and a slice of cheesecake. These lasted me several days. It turned out that a son of one of my neighbours in Kham had become a merchant’s assistant, and it was he who had sent it to me. I tell you all this not to show you how great I was, but simply to explain how I lived. I had only two choices - either to give up all my studies and religious practice, or to forget about earning a living. If I had gone out to find work, the purpose of leaving my comfortable home would have been forsaken. So I continued with my studies, regardless of how I lived - and was quite happy to do so. Why? Because each time I learned something new, I experienced great joy. I often ran into difficulties in understanding, but whenever this happened, I turned to my teachers, and they always brought me through. When I did become depressed about my poverty, I would read the biographies of Milarepa and Jé Tsongkhapa and this would console me.

Disciple: Could you not have earned a little money during the interims?

Geshé: No, these were not simply vacations. There were seven major periods of debate, each lasting one month and followed by an interim. The latter was the time for memorizing texts, which would be examined and analysed during the major periods of debate. During these interims, there would also be debating in our house from eight to eleven o’clock in the morning, and from four-thirty until six-thirty in the evening. This was true in other houses as well; but ours was especially strict. Sometimes learned monks from these would come and answer questions in debate with us, from evening until dawn. At other times, there would be no debates; and I would spend the day memorizing. Then I would recite these texts, from memory, from sunset until sunrise the next morning.

Disciple: What subjects did you study after graduating from the Collected-Topics classes?

Geshé: We first studied the perfections, primarily on the basis of the scripture The Ornament of Clear Realization, in which the subjects dealt with are very vast and profound. We studied its seventy most important points, the five progressive paths towards the liberation of the hearers (śrāvaka) and solitary realizers (pratyeka), as well as the five bodhisattva paths and ten spiritual levels. All the teachings of the Buddha are included in the three Wheels of Dharma. Among them, the middle or second Wheel is the most extensive and profound, and all of its teachings are included in The Ornament of Clear Realization. The methods for attaining the states of enlightenment of a hearer, solitary realizer and buddha are all included, starting from the practice of devotion to the guru, leading up to a description of a buddha’s body, speech and mind. This was my first formal study of the great sutras spoken by the Buddha. My method for gaining insight into them when I encountered difficulties was to consult the commentaries on them written by Indian pandits. If the meaning was still unclear, I would look to the works of Jé Tsongkhapa and his disciples. This was because Jé Tsongkhapa, a manifestation of Mañjuśrī, never wrote with uncertainty or vagueness. He was never dogmatic; instead, after gaining insight into a subject, he would write from his own experience. This is what makes his works so convincing. He was so learned that it became a proverb among the pandits of Tibet: ‘If you cannot decide, ask Jé (Tsongkhapa)’. This is as true today as it was then. Another old axiom is ‘If you cannot find the sources, look to the works of Bhu’, referring to Bhutön Thamché Khyenpa, who was a pre-Tsongkhapa master known for his extensive knowledge of the scriptures. It is never forgotten, however, that the source of all the scriptures is Buddha Śākyamuni. There can be no mistakes in his teaching. This is because errors arise from mental distortions and obscurations, and Buddha’s mind, having been purified of all distortions and obscurations, pervades all that exists. Thus, there can be no greater guide on the path to enlightenment. Because he taught out of compassion for all creatures, seeking only to serve others, with never a thought for fame or offerings, he is known as the Unsurpassable Teacher. His teachings were not collected from here and there, but arose from his experience gained by overcoming his obscurations. Methods of healing the ill are as numerous as the varieties of ailments. Likewise, since the dispositions, goals and capacities of sentient beings are limitless, so too are his methods of teaching.All the kinds of teaching he gave can be classified into the divisions of sutra and tantra. Everything in the sutras is found in the teachings given during the three turnings of the Wheel of Dharma. When you fail to understand something taught in the sutras, you refer to their commentaries; particularly to the Five Treatises, which deal with all the teachings of the three turnings of the Wheel of Dharma. Although these five are very concise, their meaning is vast. Their names are:

- Entering the Middle Way

- A Complete Commentary on Ideal Perception (pramāṇa)

- The Ornament of Clear Realization

- A Treasury of Phenomenology

- A Compendium of Discipline

There are about two hundred volumes in the collection of commentaries translated into Tibetan, which are keys to understanding all that is contained in the collected discourses of Lord Buddha. The Five Treatises are the basic source references, and the rest of the commentaries are elaborations on them. Other texts, such as the Thirteen Great Treatises and the Six Treatises of the Kadam Tradition, are all secondary to them.

Disciple: What kind of a daily routine did you follow during the fourth class?

Geshé: I can tell you what I and the other monks in my college did, but our routine was different from that of the other two colleges in Sera. Every morning, I rose at four o’clock and made prostrations until around five-thirty. Then together with all the other monks I would go to the general assembly hall where we would pray until seven o’clock or so. After this, we would go to our respective grounds and debate until ten o’clock. Sera Monastery lies at the foot of a mountain; when it rains, water runs down a ravine and flows along a normally dry riverbed running diagonally through the monastery walls. All of the monks in this college would debate in their classes at progressive points along the riverbed, the lowest class being the furthest down. From our house, there were 115 monks in the fourth class, but there were many others from the rest of the quarters in Sera Jhé. In these classes there were monks from all over Tibet, Ladakh, Mongolia and even from Japan. When we came to debate, we were never allowed to bring books or references; so any citations from the scriptures had to be given from memory.At ten o’clock, all the Sera Jhé monks would return to their assembly hall to drink tea and recite prayers, or to read passages from the Indian commentaries. Around eleven o’clock, we would return to the riverbed to debate for about half an hour; then all the monks of Sera Jhé would gather in the more formal debating ground by their own hall. There we would recite the Heart of Wisdom Sutra and read the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in 8,000 Stanzas or works by Jé Tsongkhapa and his two chief disciples. This was again a means of study and not simply a recitation. At twelve o’clock, everyone would pair off and debate; but this time, since the classes were mixed, it was likely that a beginner would have a very advanced partner. After an hour or so, we would all return to the riverbed to leave our maroon capes in their proper places, then go to our respective houses for lunch. That was the time when I would dine on my herb tea. Around one-thirty, we would again gather on the riverbed and debate until five o’clock. Then we would go to the formal debating courtyard for prayer. At this time, we would always recite by heart the ‘Prayer to the Twenty-One Tārās’ and the Heart of Wisdom Sutra. The reason for reciting the Tārās prayer is that she is the embodiment of all the buddhas’ virtuous actions and was the meditational deity of most of the Indian Buddhist pandits. This is because she is very helpful in bringing swift progress and fulfillment in one’s spiritual practice. The sutra is recited because it deals solely with emptiness, and reading it is most beneficial to one’s understanding. It is so short that one can read through it in three minutes. But when we chanted it in a manner conducive to meditation, we used such a slow, ponderous rhythm that it took longer than the time to go to Lhasa and back, or about two hours. Normally, an elder-monk acting as disciplinarian was there to see that the monastic discipline was upheld. But during this chanting, he would generally sit quietly in a corner so that he did not disturb anyone meditating. This period was extremely beneficial. It gave me time to organize things that I had learned from the day’s debating; the rhythm was so slow that it was possible to practise non-conceptual meditation on emptiness. Many other monks did the same. After this, a short mixed debating session would be held. During such sessions I would earnestly pray that all the hundreds of monks present would dispel the inner darkness of ignorance and gain great understanding. As soon as it got dark, we were allowed to stop whenever we liked; but sometimes two very intelligent, equally-matched monks would continue debating, because neither could defeat the other. When this happened, many others would gather round and listen with delight. Then after returning to our own houses for a short period of prayer, we would all leave our capes in our rooms and go to our respective teachers. This evening lesson took an hour, following which we would all go to the formal debating courtyard, divide into our classes and again debate. The special purpose of this session was to go over the lesson just given in order to fix it firmly in mind. Although most of the monks could do as they liked at the end of this session, those in the fourth class were required, on alternate nights, to remain all night in the college courtyard, debating without a break. On those nights when we did not debate, the monks in the Beginning Mādhyamika class would hold similar sessions. I found these all-night debates very difficult, especially in the winter, when the wind and snow were biting cold. My hands would become hard from the clapping, and would crack on both sides and then begin to bleed. This debating ground was roofless and lit by a few butter lamps, which always died out around the middle of the night.

Disciple: During the periods when there was so much time spent in debate, how did you manage to recite the texts you had memorized?

Geshé: We would recite on the nights when the Beginning Mādhyamika class was debating, but there was not much time to memorize fresh texts.

Disciple: Did all the monks in this class debate all night?

Geshé: No, everyone paired off for debating only during the mixed sessions. The rest of the time, there would be two answerers and one questioner, while the remainder would listen and add their own comments from time to time. Since my robes, unlike most of the others’, were very ragged, while listening I used to bury myself up to the waist in the sand, which was still warm from the day’s sun. But despite the hardships, I never felt any reluctance to attend; nor did I become bored or depressed.

Disciple: Were the interims during the Beginning Treatises class like the previous ones?

Geshé: Not exactly. There were still seven periods of debate per year, each lasting from roughly three to six weeks; but after graduating into the Perfections classes, which included the fourth to the eighth; we were allowed greater freedom during the interims. Whereas previously we had been confined to our own house at night, after graduating to the fourth class, I often used to go into retreat during the interims, as my house would be very crowded. I sometimes stayed in other houses that were quieter than mine, or stayed in caves on the mountain above Sera. This was very conducive to spending a lot of time memorizing; so I usually lived outside my own house during these periods.

Disciple: How did you spend your days during these interims?

Geshé: Sometimes I remained in strict meditational retreat for several weeks. During these times, I rose early in the morning, and meditated during four periods of each day. While practising the developing stage of tantra, involving the meditational deities Yamāntaka or Vajradākinī, I read many related texts between meditation periods. These eventually helped to enrich my meditation. During other retreats, I practised the life-increasing meditations of White Tārā and Amītābha, and other meditations involving Vajrasattva, guru yoga, the stages of the path and so on. Many monks engaged in such retreats in groups, but I always did so in solitude. During other interims, I devoted myself primarily to memorizing texts. I would spend all morning at this; then after lunch I would go to receive instruction from my guru. During debating periods, such instruction was given only occasionally, for the emphasis was on investigating the material which had been memorized and explained by one’s teacher. After graduating into the higher classes, I gave daily instruction to a number of disciples during the interims, receiving less frequent teaching from my own guru. More time was given to memorization after these lessons; then when the sun set, I began reciting those texts I had just memorized. At first, I used to memorize one side of a page a day, then gradually I worked up to two, then four sides. Although it was difficult at first, I, like the other monks, gradually became accustomed to it, so that both memorization and recitation came with ease. In the Western academic tradition, note-taking plays a vital role, and much of one’s knowledge tends to be confined between the covers of one’s textbooks. Our corresponding stores of knowledge were held in our minds, through memorization. Sometimes I recited from sunset until sunrise. But on other occasions I spent only part of the night in recitation, then filled the remaining hours before dawn making mandala offerings and performing prostrations. Many people working in a factory have nothing to occupy their attention but their daily routine. Similarly in the monastery throughout the day and night, I had nothing to think of but the practice of Dharma. Because I could not get much food during the interims, I used to gather a kind of grass that was known to contain poison and make a stew out of it. This, though it deadened my mouth, filled my stomach; and it actually helped my digestive heat, which was generally poor from lack of food. Occasionally, other monks who realized how poor I was would give me a little food and tea. Sometimes during the breaks, there would be debating sessions in my house; these I would never miss, as I found them so helpful.

Disciple: What was the primary source of your enthusiasm and perseverance in the practice of Dharma?

Geshé: I was motivated by a great desire to increase my understanding of Dharma, which led me to work very hard at memorization and debate. And since such growth of understanding requires purification of harmful mental imprints and obscurations, I made many mandala offerings and prostrations towards this end. When such a desire is very strong, one pays little heed to physical hardships. Similar cases are found in the West. It often happens that people running a business become completely enraptured with the thought of how much money they can make. The hardships they undergo to realize such profits are amazing.

Disciple: When did you receive the full monastic ordination?

Geshé: When I was in the Beginning Treatises class, I received the vows of a fully ordained monk from Phurchog Jhampa Rinpoché, who had previously given me the novice ordination.

Disciple: Did you have to pass a special examination before being allowed to graduate from the Beginning Treatises class?

Geshé: No, the next examination was given during the Advanced Treatises class. At that time, we were examined on the extent of our understanding and memorization of the scriptures. To check our comprehension, the abbot and disciplinarian listened to us debate; then to show how much we had memorized, we recited the texts we knew by heart. Only the top-ranking students were given grades. The abbot gave them the honour of reciting and debating in a formal ceremony. The first and second students of the class were traditionally given the buddha nature as their topic. The top student must either compose or adopt a dissertation on this subject, then recite it in a specified rhythm; his debating partner is the student with second highest. I was given the third highest grade, and ‘the path of preparation’ as my dissertation topic. My debating partner, the fourth-grade student, and I then had to visit each of the nine higher classes, starting from the Beginning Separate-Topics class. We visited one of these each day and were tested by them on this topic. Those nine days were really difficult, as those in the higher classes were very learned and really put us through it. During the interims, I had to visit the eight major houses and was again tested on this. In each house I was questioned by monks, ranging from old Geshés to new students. These times were also very difficult, for not only did my examiners chew me up, but in summer there would be fleas on the seat, and they did their share of chewing, too. Some of my questioners kept me up only half the night, but others examined me until dawn. After all this, I had to attend the formal examination in the college assembly hall, where I sat before all the six thousand monks of the college to recite my dissertation. In this I had to explain how the path of preparation is discussed in the Buddha’s discourses, the commentaries by Indian pandits, and the works of Jé Tsongkhapa and his two chief disciples. On the basis of these I explained the nature, divisions and types of meditation involved on this path. Afterwards, I had to answer the questions put to me by my debating partner. This recitation and debate took about three hours.

Disciple: Was the daily routine of the rest of the Perfections classes about the same as that of the fourth?

Geshé: For one year, we studied the Cittamātra section of Jé Tsongkhapa’s great treatise The Essence of Good Instruction, on the interpretation of the sutras; and then for another year the twelve links of dependent origination, the foundation consciousness, and the development of mental quiescence (śamatha). In the beginning, I made extensive studies of the seventy ways of understanding and attaining the various stages on the path to enlightenment, as well as the qualities of a buddha. These deal somewhat with emptiness, but mainly with the method aspect of the Dharma. Included in these seventy are:

- The ten ways of understanding and attaining a buddha’s wisdom.

- The eleven ways of understanding the wisdom gained from the Mahāyāna path of seeing, up to enlightenment.

- The nine ways of gaining the wisdom of identitylessness and impermanence.

- The eleven ways of understanding the wisdom of the bodhisattvas from the path of accumulation, up to and including the end of the continuum of existence as a sentient being (as opposed to a buddha).

- The eight ways of gaining the wisdom of the Mahāyāna path of preparation, up to and including the end of this continuum.

- The thirteen ways of gaining the wisdom of the Mahāyāna path of accumulation, up to the end of this continuum.

- The four ways of gaining the wisdom of the final stage of a bodhisattva.

- The four ways of gaining the wisdom of understanding the omniscient mind of a buddha.

Then I studied in detail the fundamental text of these seventy ways, which deals with the teachings of the second turning of the Wheel of Dharma. It is based on the tenets of the Svātantrika school and deals more with method than wisdom; or in other words, the extensive rather than the profound aspects of the teachings. For about a year, I also studied the two realities and the foundation consciousness, etc., according to the tenets of the Cittamātra school. During these five Perfections classes, a complete, broad and profound understanding of the stages of the path to enlightenment is gained. This gives one a limitless amount of material on which to meditate. One’s knowledge is then like a big department store - from it one can buy anything one wants, and as much as one likes. Upon completing these five classes, one is familiar with the systems of thought of all the philosophical schools of Buddhism.

Disciple: Does one not forget the subjects studied a few years earlier?

Geshé: No, old subjects are not forgotten, because they are debated again and again during the breaks; this gives one an even better understanding of them than before.

Read more: http://www.thlib.org/places/monasteries/sera/#essay=/cabezon/sera/lifeofseramonk/s/b3#ixzz0Wuy2DxAd

Read more: http://www.thlib.org/places/monasteries/sera/#essay=/cabezon/sera/lifeofseramonk/s/b3#ixzz0WuyKlNUw

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario